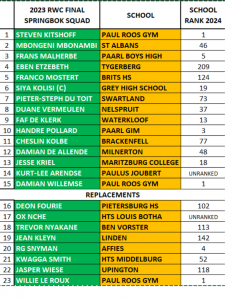

Below is the match-day squad for the 2023 Rugby World Cup final. There is also the school that the player attended and the school’s ranking at the end of the 2024 season.

The strength and success of the Springboks, 4-times Rugby World Cup winners, is often linked to South Africa’s much vaunted schools’ rugby system. The understanding is that there is a clear link between the level of rugby played in schools and the success of the national team. How sustainable is the South African schools’ rugby system in terms of producing generational Springboks? Should we rest on our laurels because we are current world champions, or should we interrogate current trends to ensure future success?

The strength and success of the Springboks, 4-times Rugby World Cup winners, is often linked to South Africa’s much vaunted schools’ rugby system. The understanding is that there is a clear link between the level of rugby played in schools and the success of the national team. How sustainable is the South African schools’ rugby system in terms of producing generational Springboks? Should we rest on our laurels because we are current world champions, or should we interrogate current trends to ensure future success?

Schools’ rugby has undergone fundamental shifts over the last 5 years, becoming increasingly professionalized, with greater concentrations of power and wealth in schools that are typically ranked in the Top 20. However, there has as yet been no response to these shifts from those who are tasked with guarding the future of the game in the country, namely SARU and SASRA.

Schools outside the Top 20 have found themselves under ever-increasing pressure as their player-resources have been plundered by schools with wealth and power. Top 20 schools call the practice ‘scouting’ while the schools who are plundered call it ‘poaching’. Outside of the Western Province schools’ league – where a framework has recently been introduced to manage learner movement between schools – the governing authorities have been silent as the game in schools has undergone radical changes. What will the consequences be if there are no fundamental systemic shifts in how the schools’ game is governed?

Firstly, there will be an ever-increasing concentration of wealth and power in the top 10 to top 20 schools. This will in all likelihood end up as a semi-professional league featuring schools in the top 20 that will resemble a Varsity Cup-type tournament. Secondly, schools outside of this elite group will find it ever harder to put together meaningful rugby programmes, where young players are exposed to high quality coaching and development. Will this impact Springbok rugby? In the long run the table above suggests that it will and should be of significant concern to those governing the game.

From the table above we see that 57% of the Springboks who won the 2023 Rugby World Cup attended schools that in 2024 were ranked outside of the Top 40. Let that sink in for a moment. 30% attended schools who are ranked outside the Top 100.

Springbok rugby is strong not because we have 10 to 20 elite schools playing the game but because we have over a hundred schools with meaningful rugby programmes. These are the schools that rugby authorities have to protect – and they need to be protected with new, well thought out rugby-related legislation.

Those with wealth and power will continue to act in their own self-interest, it is the way that society works. However, governing authorities and legislative frameworks are there to ensure that this self-interest does not do damage to other sectors of society – and therefore damage to the ‘collective’, in this instance the national game.

Regarding the movement of schoolboy rugby players, it is painfully obvious that a new legislative framework is long overdue. Primarily this should be done to safeguard rugby programmes across the entire spectrum of schools’ rugby, which in turn sustain the long-term success of the national side over many decades.

Here’s one option:

If School A would like the services of a player who is School B, then School B must sign a letter of release to formalize the process. If required, School A must compensate School B for the time and finances that have been invested in that player. School B (generally outside the Top 20) can then use this capital to invest in their rugby programme to ensure its future success.

Here’s another:

Ban ‘scouts’ and ‘agents’ from interacting with schoolboys until after Craven Week in their matric year. Scouts generally have one priority and that is filling their own pockets. They have no concern for the damage that they do to individual schools when they manipulate boys to move away to schools with more wealth and power. They must be prevented from doing so by law – if there is the will to protect as many rugby programmes as possible and therefore the long-term future of South African rugby.

The table also gives truth to the lie that boys have to attend a Top 10 school to become a Springbok. This untruth is often peddled by ‘scouts’ and ‘agents’ and repeated by those with a vested interest to entice boys away from rugby schools outside the Top 20. However, the evidence is clear, you can become a Springbok at any school that offers a meaningful rugby programme – even those ranked outside the Top 100. The critical fact is that these schools must be left alone to thrive in their own space and not be undermined by those who have no concern for their future success.

There are other options available, but don’t get caught up in the detail. The key point is that rugby authorities are watching a process unfold that is going to undermine the future success of both the entire schools’ rugby system, as well as the long-term success of the game at a national level.

Schools’ rugby is also about more than performance on the field – it is deeply connected to the life of the whole school, in identity, culture and school pride. Rugby therefore has the ability to impact every corner of school life. In protecting rugby programmes across the entire spectrum of rugby-playing schools in South Africa, we will also be protecting these schools being ‘special places’ that build South African society.

The issues, although complex, are clear. We ignore them at our collective peril.

Contributed by Andrew Swift

Educator and rugby coach